Dr. Copper Is Now the Bug Slayer

April 06, 2020

Read Time 4 MIN

Dr. Copper is a conceptual term used for copper because of its ability to predict turning points in the global economy. This term, Dr. Copper, is equally relevant when thinking about the critical role copper plays in decarbonization (see Copper Demand Is “Electric”—But Can Supply Keep Pace?). Now however, with the onset of COVID-19, can Dr. Copper also rightfully reclaim the name "bug slayer"?

Copper has always been well known for its ability to fight viruses and bacteria: ancient Egyptians used copper to help sterilize their drinking water. Hippocrates, the "father" of modern medicine (see “Hippocratic Oath”), recommended copper for various diseases. The Aztecs used copper for medical purposes, including gargling with copper-infused water to combat sore throats and infections.

With the onset of COVID-19, the potential use of copper in a range of settings is undoubtedly going to receive renewed attention.

Dr. Copper?

The antimicrobial properties of copper can kill up to 99.9% of some bacteria, including several superbugs resistant to antibiotics, within two hours. Upon contact with copper surfaces, bacteria, yeasts and viruses are quickly killed. The process involves the release of copper ions (electrically charged particles) when microbes land/are deposited on its surface. The copper ions punch through the outer membranes completely, destroying the whole cell, including the DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) and RNA (ribonucleic acid). Because the DNA and RNA are destroyed, bacteria or viruses can neither mutate nor become resistant to the copper.

There is a significant amount of evidence to show that uncoated copper and/or copper alloy surfaces can significantly reduce the spread of microbes such as, norovirus, MRSA, E. coli and coronaviruses.

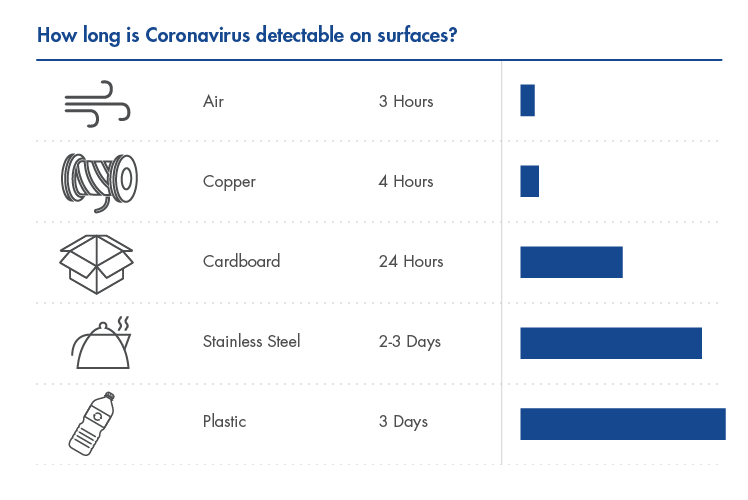

A recent study by the National Institute of Health (NIH), CDC, UCLA and Princeton University1 found that the COVID-19 virus can remain on surfaces for hours. According to the study “scientists found that severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SAR-CoV-2) was detectable in aerosols for up to three hours, up to four hours on copper, up to 24 hours on cardboard and up to two or three days on plastics and stainless steel”.

It would appear, therefore, that the spread of a virus can be significantly enhanced by the extensive use of stainless steel and plastic in modern day societies.

A new study published in Applied and Environmental Microbiology2 found that copper hospital beds in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) had about 95% fewer bacteria than a conventional hospital bed. Another study in Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology3 shows that hospital-acquired infections cause an estimated 100,000 deaths annually, partly because bacteria are increasingly becoming resistant to regular treatment, but that copper may put a stop to this.

Its use within the healthcare service industry will surely gain momentum, as it has at Santiago's General Hospital in Santiago, Chile. (See CNN video on YouTube). According to an article in The Washington Post4 back in September 2015, fifteen hospitals in the U.S. had been, or were, considering installing copper on surfaces such as faucets, sinks, door handles, railings, call and elevators buttons and IV poles, to name a few potential applications. Furthermore, currently great strides are being made to introduce copper’s antimicrobial properties into face masks.

Although the benefits of copper-alloy surfaces in healthcare facilities are apparent, the potential of the application is, in fact, much broader.

Here are just a few of these broader applications: Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport installed drinking fountains with antimicrobial copper surfaces. Similarly, airports in Brazil have installed copper surfaces at their check-in, customs and immigration counters (see photo). Fitness centers have turned to antimicrobial touch surfaces, such as at the U.S. Olympic Committee’s training center in Colorado Springs. Likewise, the Los Angeles Kings and St. Louis Blues have installed copper in restrooms and on door handles.

Antimicrobial copper counters at Congonhas Airport in São Paulo, Brazil

Source: Copper Alliance

Finally, back in Chile, Fantasilandia (in Santiago), one of the largest theme parks in South America, has replaced most frequently touched surfaces with copper. (As an aside, now you can even buy a copper patch to stick on the back of your cell phone to help ensure that it can become less of a bug carrier!)

Why the Absence of Bug Fighting Copper?

Historically, one of the main reasons has probably been price: the cost of copper has been perceived as outweighing the benefits to be gained from its use. With healthcare costs constantly on the rise, however, this point may now have become increasingly moot. In a 2015 study, the math showed it could be cost effective even back then. When looking at healthcare-associated infections (HAIs), researchers estimated that the time to recoup the cost of installing antimicrobial copper components in a hospital could be less than two months.5

Other reasons copper has not been used are really rather more mundane, but probably just as significant. Glass, plastic and steel do not tarnish, regardless of how filthy, on a microscopic level, their surfaces may actually be. Copper, on the other hand, tarnishes easily and requires a lot of cleaning to remain shiny, even though it never ceases to be an effective “bug buster!”

Conclusion

Copper is widely used across many industries, from construction and electronics to transportation, but one property that makes it especially attractive is its bug fighting capability. A new role for Dr. Copper as bug buster? We certainly think the idea should seriously be entertained—once again. It has been used as one throughout the ages and appears only relatively recently to have fallen out of favor.

As is to be expected, copper usage in the healthcare industry is relatively small (about 100,000 tonnes per year). However, its potential usage could become an important demand driver if it replaces, or even partially replaces, the use of stainless steel in the healthcare industry. Within the healthcare industry, stainless steel demand is estimated at approximately 2.5 million tonnes per year. While it is unrealistic to think that all stainless steel would be replaced, even if only 25% were replaced with copper, it could translate into approximately 3% in new demand. This additional demand would be significant enough to make a marked difference to the supply and demand fundamentals in the copper market.

Although we cannot know just how much copper’s increased use in this context might add to demand, if nothing else, what is demonstrated, once again, is just how essential copper is to humanity’s wellbeing.

Paging Dr. Copper….

DISCLOSURE

1Aerosol and surface stability of HCoV-19 (SARS-CoV-2) compared to SARS-CoV-1: N van Doremalen, et al., The New England Journal of Medicine. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973 (2020).

2Self-Disinfecting Copper Beds Sustain Terminal Cleaning and Disinfection Effects throughout Patient Care, Self-Disinfecting Copper Beds Sustain Terminal Cleaning and Disinfection Effects throughout Patient Care: Michael G. Schmidt, Hubert H. Attaway, Sarah E. Fairey, Jayna Howard, Denise Mohr, Stephanie Craig, Applied and Environmental Microbiology Dec 2019, 86 (1) e01886-19; DOI: 10.1128/AEM.01886-19

3Copper Surfaces Reduce the Rate of Healthcare-Acquired Infections in the Intensive Care Unit: Salgado, Cassandra D., Kent A. Sepkowitz, Joseph F. John, J. Robert Cantey, Hubert H. Attaway, Katherine D. Freeman, Peter A. Sharpe, Harold T. Michels, and Michael G. Schmidt. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology 34, no. 5 (2013): 479-86. Accessed March 26, 2020. DOI:10.1086/670207.

4The bacteria-fighting super element that’s making a comeback in hospitals: copper: Lena H Sun, The Washington Post, September 20, 2015.

5From Laboratory Research to a Clinical Trial: Copper Alloy Surfaces Kill Bacteria and Reduce Hospital-Acquired Infections: Michels HT, Keevil CW, Salgado CD, Schmidt MG. HERD. 2015;9(1):64–79. doi:10.1177/1937586715592650

The information presented does not involve the rendering of personalized investment, financial, legal, or tax advice.

Certain statements contained herein may constitute projections, forecasts and other forward looking statements, which do not reflect actual results. Information provided by third-party sources are believed to be reliable and have not been independently verified for accuracy or completeness and cannot be guaranteed. Any opinions, projections, forecasts, and forward-looking statements presented herein are valid as of the date of this communication and are subject to change without notice. The information herein represents the opinion of the author(s), but not necessarily those of VanEck.

The views contained herein are not to be taken as advice or a recommendation to buy or sell any investment in any jurisdiction, nor is it a commitment from Van Eck Associates Corporation or its subsidiaries to participate in any transactions in any companies mentioned herein. This content is published in the United States. Investors are subject to securities and tax regulations within their applicable jurisdictions that are not addressed herein.

All investing is subject to risk, including the possible loss of the money you invest. As with any investment strategy, there is no guarantee that investment objectives will be met and investors may lose money. Diversification does not ensure a profit or protect against a loss in a declining market. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Related Insights

Constrained supply conditions, disruptions in the supply chain and growing interest in the global energy transition global energy transition may result in a significant upturn for global resource equities.

April 18, 2024

April 15, 2024

March 21, 2024

January 22, 2024